The Colonial Scissors: Cutting Art from Craft

For centuries, beauty and function were married in our homes. The pitcher was created for water and for poetry; the blanket was for warmth and for story. This unity was disrupted when the colonizer arrived with a new rulebook. We inherited the colonizer's categories of "Art" and "Craft" as if they were universal truths, but they are not.

This hierarchy was a deliberate, ideological project of colonialism. By elevating European painting and sculpture, the "Fine Arts" as the pinnacle of intellectual and spiritual achievement, and simultaneously demoting the integrated, functional creations of colonised cultures to "mere craft," a powerful value system was enforced. This was not simply a matter of taste; it was a mechanism to devalue entire worldviews where beauty, utility, and spirit were inseparable.

This schism remains the "ghost in the machine" of our contemporary art markets, museums, and interior design choices.

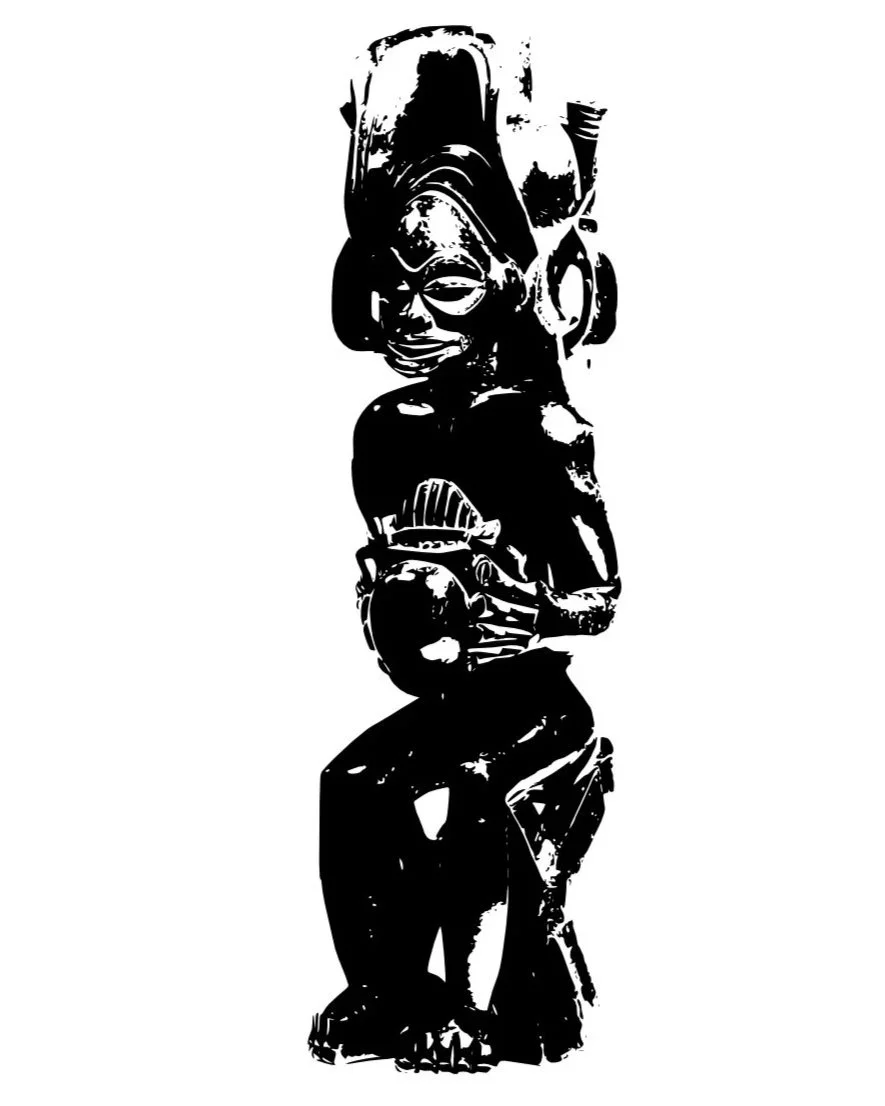

How do you devalue a people? You erase their creators. The colonial gaze refused to acknowledge the individual artisan. Instead, it saw a specimen: a representative of a "caste," a "tribe," or a "folk tradition".

This erasure is evident in the museum label. For a Rembrandt, the label provides a biography. For a Congolese power figure, it often reads simply, "People of the Lower Congo, 19th Century".

This is not an oversight but the logic of colonial dehumanisation in practice, where Brown individuality is erased to fit a narrative of a static, collective "Other".

* Mwanangana (lord of the

land) playing a sanza -

Chokwe artist 19th century

Straight out of the neocolonial playbook is an insidious circuit of validation, a pattern of cultural arbitrage that permeates the globe. It operates in three stages:

Internal Devaluation: Urban elites within the culture view their own traditional crafts as "backward".

Revival for the Gaze: The craft becomes "cool" only when revived in a form that suits the Western aesthetic. It is often simplified, "beige-washed," and stripped of its meaning, while the artisan remains unknown. The value is assigned by the center, not the source.

External Validation Trigger: A Western brand, museum, or celebrity "discovers" it.

Prada-fied Kolhapuris: For generations, sturdy, beautiful leather sandals were made by artisans in Kolhapur, locally valued but globally ignored. Enter Prada, and suddenly it is a "new" trend, with the value now decided by Milan.

Even the humanitarian framework can perpetuate this dynamic. NGOs, often reliant on donor narratives, market artisans as victims to be "saved" rather than masters to be partnered with.

This creates pressure to perform the role of the "native informant", a simplified identity that satisfies the Western consumer's desire for a story of rescue rather than creative agency. The complex reality of the artisan-entrepreneur is lost in favor of a palatable tale of tradition and poverty.

Furthermore, the globalized aesthetic of "sophistication", characterized by the minimalist apartment and the "less is more" ethos, stands in opposition to an "Aesthetic of Integrated Abundance". For many cultures, visual richness (layered patterns, vibrant colors) is not "clutter" but a lived philosophy where space is alive with narrative and connection. Adopting minimalist standards is often a quiet acquiescence to a worldview that alienates a cultural logic of beauty that finds holiness in the ornate, the lived-in, and the abundant.

This devaluation is also profoundly gendered. The crafts most associated with the domestic sphere, weaving, embroidery, pottery, were predominantly women's work. Feminist economist Maria Mies termed this process "housewifization": the systemic rendering of women's labor as non-productive, informal, and supplementary. A dowry chest, meticulously embroidered over years, was seen as a natural duty rather than a transfer of economic and cultural capital. The dismissal of craft is inextricably linked to the dismissal of women's intellectual and creative contributions.

The colonial project separated the hand from the mind, and the object from its story. Our work is to weave them back together. To recalibrate the gaze, we must:

Credit as a Political Act: Seek and state the name of the maker. Reject anonymity.

Question the Hierarchy: Challenge assumptions when a painting is called "visionary" while a textile is merely "charming".

Embrace the Hybrid: Support contemporary artisans who are innovating within their traditions, not just performing them.

Decolonize Your Curation: Fill spaces with objects that speak to heritage and complexity, not just an imported ideal of tranquility.